The ownership of Strážky Mansion was transferred to the Slovak National Gallery after the death of its former owner, Baroness Margita Czóbel in 1972. The SNG subsequently carried out its reconstruction, together with the renovation of the 19th century English park, where it installed an exposition of 20th century sculptures.

The permanent expositions are situated on its exhibition premises where various musical, theatrical and educational events are also held. Permanent expositions feature the paintings of Ladislav Mednyánszky, portrait paintings from the Spiš region, collections of the historical library and the mansion furniture.

Strážky mansion, together with the late-Gothic Church of St. Anna and the Renaissance bell tower – serving as watch tower (1629), comprised one urbanistic unit which was later separated by the road between Kežmarok and Stará Ľubovňa.

The mansion did not achieve its present appearance until the 16th – 17th century, when it was gradually transformed into an L-shape building with protective elements and attic, which was characteristic for the Renaissance buildings of Eastern Slovakia.

The fourth wing was added around 1850, while the Romantic element was emphasized by the English park which was designed in accordance with the period fashion. The Mednyánszky family was so intent on preserving the integrity of the estate that it funded the construction of the railway bridge over the Poprad River in order to divert the route which was originally intended to pass through this park.

Due to the turbulent events after 1948, the interior of the mansion was not preserved despite the tremendous efforts of its last inhabitant, Baroness Margita Czóbelová. Only some built-in cabinets, chests, porcelain and clothing remained. As a result, the exposition was complemented by furniture from SNG collections, period chandeliers from the Bratislava City Museum and other artefacts.

Family Gallery

The family gallery was created at the beginning of the 18th century and features domestic paintings from the late Renaissance up to the end of the Romantic era in the 19th century. The portraits of the Horvath-Stansith family, for whom Johann Gottlieb Krammer (1716 – 1771), one of the most significant figures on the domestic art scene also worked in the 18th century, are the oldest of the collection. We can also find portraits of the later owners of the mansion – the Szirmay family, the Mednyánszky family, the Czóbel family and their more distant relatives.

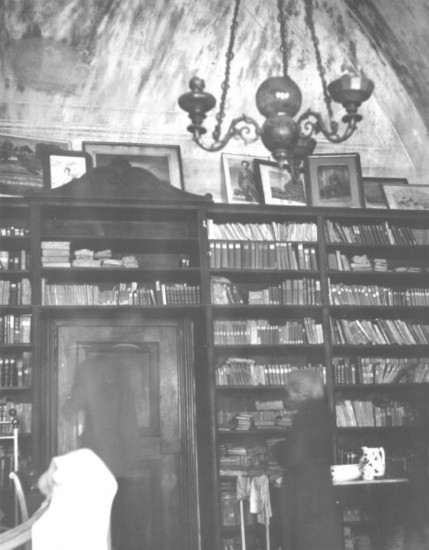

Humanistic Library

The family library was established for the needs of the humanistic school which was founded at the end of the 16th century. Members of the Horváth-Stansith family gradually added books acquired during their studies, frequently at foreign, especially German universities. The catalogue from the end of the 18th century mentions the works of ancient and Renaissance authors and literature from the period of the Enlightenment, particularly biographies and books related to history, philosophy and freemasonry.

Many books were also donated by Baltazár Szirmay. The list of books that he purchased from 1836 to 1844, mostly literature from the 16th to 18th centuries, was preserved in the archives.

The last library catalogue was compiled in 1875 thanks to the efforts of Eduard Mednyánszky, the father of Ladislav Mednyánszky, and contained more than 6,300 books. Today the library has approximately 8,420 books, magazines and maps.

Exposition of Ladislav Mednyánszky and Strážky Mansion

This mansion is famous for its permanent exposition of the paintings of Ladislav Mednyánszky (1852 – 1919), whose life was closely connected with this space. Although he was originally from Beckov, it was here at the foot of the Tatras where he found excellent conditions for searching for his own artistic style in the early stages of his career.

Strážky later became the place where he painted and stored his works, where he rested from the busy environment of Viennaand Budapestand where his only permanent studio was situated.

The Life of Mednyánszky

The artist was born on April 23, 1852 in Beckov. He was the son of Eduard Mednyánszky and Mária Anna, nee Szirmay, who lived in the manor house in Beckov. They frequently visited Baltazár Szirmay, Mária Anna’s father, at the mansion at Strážky, and permanently moved there after Szirmay’s death in 1862.

The strong personality of the grandfather, a man who read and traveled extensively, also influenced the young Mednyánszky. Both helped people in need and travelled extensively. And like his grandfather, Mednyánszky kept a diary in Hungarian and German, but using the Greek alphabet.

In 1863, Thomas Ender (1793 – 1875), an important Austrian landscapist, became acquainted with Mednyánszky during a visit to Strážky. He became interested in the development of this talented young man and sent him plaster casts from Vienna and later corrected his first drawings.

Mednyánszky’s further training continued in 1872 – 1873 at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich and later at École des Beaux Artes, Paris. He completed his art training in 1875 in Paris, the mecca of art at those times, where the influence of Barbizon was gradually fading and Impressionism was on the rise.

The Work of Mednyánszky

The collection at Strážky features the two main streams of Mednyánszky’s work: landscapes that captured the wilderness and beauty of the Tatras and the many portraits of simple people, peasants, soldiers, frequently physically strong types. Several of his friends whom he mentioned in his diaries were also of simple origin. Mednyánszky lived his life as a wanderer, and Strážky and Beckov represented his only fixed points.

The key periods in his artistic career were at the end of the 1870s when he applied the knowledge from France to the themes from his surroundings and the 1890s, when he returned to Strážky (1892) after a longer stay abroad (Paris, Vienna, Budapest). His paintings with melancholy and even mystical touches and which helped him cope with the loss of his father (1895), were created in this time.

In 1896 – 1897, Mednyánszky travelled through Dalmatia, Montenegro and Northern Italy back to Paris. During this (last) stay, his only individual exhibition took place in 1897 in Georges Petita Gallery, where many impressionists and modernists exhibited. After 1900, his stays in Strážky were shorter and less frequent; he spent the most of his time travelling or in Vienna and Budapest.

The works of Spiš artist Ferdinand Katona (1864 – 1932) are also exhibited on the mansion premises. Mednyánszky began supporting him at the beginning of the 1880s when Katona was an up and coming artist. Katona is considered one of the foremost Hungarian landscape artists of those times, but his work never surpassed that of his mentor.

The works of Mednyánszky’s niece, Margita Czóbelová (1891 – 1972), a gifted artist in her own right, can also be found here. In addition, she was responsible for preserving the works of her uncle during and after World War II.

The Life and Work of Margita Czóbelová

Margita Czóbelová’s artistic ambitions were hindered after World War I when she was gradually forced to take care of the entire family. Her brother Štefan got lost during the war, her sister Marianna died young in 1929 and she took care of her parents until their last days. Her father, Štefan Czóbel, a writer, philosopher and economist died in 1932; her mother, Margita (Miri) Czóbelová, nee Mednyánszka died five years later. Czóbelová endured World War II on her own, and after the political changes in 1948 she lost her property and the family’s art inheritance.

The isolation of the baroness in Strážky also affected her art work. During the interwar period, she concentrated on illustrations. She created fresh colorful compositions from the park near the mansion and landscapes inspired by the work of her uncle. Shealso did portraits of male and female members ofthe family along with self-portraits.

Less usual and expected themes from the modernized Tatras (the cable railway) and the socialist world (Lomonosov University, Sputnik, etc.) appeared after World War II. They are evidence of the fact that she remained actively interested in the world around her. As a result of the upheaval that followed the political changes of 1948, she could not preserve the interior of the mansion despite great efforts.