We have a reasonably good idea of the life of the exceptional artist and "lonely pilgrim" Ladislav Mednyánszky (1852 – 1919), thanks to his extensively maintained diaries. Issues of his private life have not yet been thoroughly researched, but we know he was attracted to men. Sometimes, the identities of several of his partners and the circumstances of their relationship are known.

Although Mednynánszky lived at a time when neither the term "gay" (the word "homosexual" was only introduced in the second half of the 19th century by the Hungarian publicist Károly Kertbeny; subsequently, this label spread to Western Europe[1]), nor any organised movement for the rights of gays and lesbians existed, and homosexual acts were criminalised, we can say that the painter led an active life in terms of relationships. However, he was largely dependent on short-term contacts and frequent travel in a permanent effort to conceal his orientation. His emotional life was marked by tragedies (the biggest of which was the untimely death of the love of his life, Bálint Kurdi) and the tension between natural needs and the ideal of a disembodied spiritual living, which the artist professed.

The sexual orientation of an artist should certainly not be the only interpretive framework of their oeuvre; at the same time, however, it is appropriate to take it into account. In Mednynászky's case, the art historians Csilla Markója, but also Katarína Beňová, have already shed light on his work from this angle. Today, we can perceive some motifs of Mednyánszky's paintings with a view enriched by other levels. For example, the motif of a chained slave is an allusion to the iconography of St. Sebastian, which was, at that time, clearly appropriated by the homosexual community. In general, it can be said that artists with a homosexual orientation used seemingly neutral motifs, such as a male act of the "Ephebe" type, to express their identity and desire in a coded manner and simultaneously communicate with an affiliated audience.

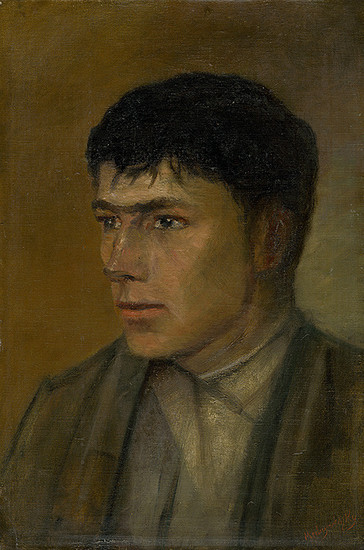

In the collections of Slovak galleries, we can find several of Mednyánszky's portraits of strikingly beautiful, strong young men. (It is worth noting that he created very few portraits of women). As a rule, these were people from lower classes — peasants, coachmen, fishermen or wanderers whom he knew from around Strážky or whom he met on one of his many journeys. As Csilla Markója writes, the dynamic transition between castes and classes (from the castle to the vagabonds) is again related to Mednyánszky's homosexuality because he often found his lovers among lower-class men. "...the experience of the periphery became for him the experience of identity..." [2] Markója thus corrects the previously preferred opinion that the painter's interest in vagabonds was exclusively an expression of empathy and criticism of their social conditions. We know from his diaries and other contemporary testimonies that Mednyánszky was of fragile health (he often mentioned various ailments), and as an aristocrat born with a silver spoon in his mouth, he admired the unchained vitality of the lower-class people. He considered them powerful and strong (as opposed to his weakness) and "animalistic" (as opposed to his melancholy). The artist perceived strength and animality as undoubtedly favourable qualities, synonyms of a natural, simple, happy experience he was not afforded. [3]

This exhibition is an accompanying event to the Rainbow PRIDE Bratislava festival.

The text was created in collaboration with SNG curator Katarina Beňová.

The exhibition cycle In the Shop Display enters the public space through the window of Café Berlinka on the ground floor of the Esterházy Palace, presenting works of visual art responding to the issues of contemporary life. In this exhibition format, we have revived collaboration between Peter Bartoš and Július Koller, who in 1968 exhibited their works in a storefront of a stocking repair shop in Klobučnícka Street in Bratislava under the title Interpretation (Anti-gallery).